Geoff Leonard

Prague - Raise The Titanic, Geoff Leonard

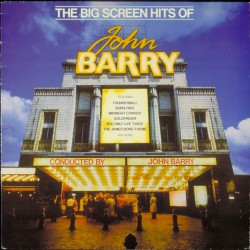

Over the last few years I have done a fair amount of work for Silva Screen. Mainly on liner notes for their John Barry and related albums, but also research. Very recently at the request of James Fitzpatrick I spent some time going through the first James Bond films, noting any notable music cues which do not appear on the official albums. James’ idea was to combine these cues with the best of the previously released material into mini-suites. Nic Raine would have the rather more exacting job of reconstructing the ‘new’ music and arranging it.

For some years now, Silva have recorded much of their catalogue in Prague, mainly due to the spiralling costs of London-based musicians and studios. To make the best use of the time and facilities over there, James always ensures there is a variety of music to be recorded – certainly enough to last for a few days. On this occasion, apart from the Bond album, he would also be recording a tribute album to Gordon McCrae and Howard Keel, using Welsh baritone Jason Howard with arrangements by Paul Bateman; a Barbra Streisand film music album (for another company) and, to my delight, Nic Raine’s reconstruction of the entire score to 'Raise The Titanic'!

Recording in Prague was set to begin on the 9th June, lasting until the 14th, and I was surprised and delighted to be asked along to the sessions. The journey from Bristol to Prague went very smoothly. By coincidence, a friend of mine was also going to spend some time in Prague, and, living only a few miles away, we were able to journey to Heathrow together.

This was the first time I had flown anywhere from Heathrow, but I had precise directions from James as to where everything was. Most of the rest of the party had already flown out earlier in the day, either from Heathrow or Stanstead, but James told me to look out for Jason, who, due to a late change of plan, would be on my flight.

After an initial frustrating delay on the plane waiting for our ‘slot’, the flight went very smoothly and lasted only one hour twenty minutes. I had a rough description of Jason but failed to spot him either on the plane or at the airport, although there was one or two who looked as though they might be him. I later discovered he thought he had seen me but was put off because I appeared to be with someone rather than on my own as he had been told. For my part, I have to say James’ description of Jason wasn’t particularly accurate!

I’d heard one or two horror stories about Prague taxis, especially their prices, but I was able to share a mini-bus with my friend who had one booked and paid for as part of his package.

I knew recording was due to start at 5 p.m. and as I didn’t get booked into the hotel until about 7.15, I decided it wasn’t worth turning up for the last half-hour. Instead I met James in the lobby about an hour later. He quickly introduced me to Jason, who I was embarrassed to discover was one of the people I’d been staring at at Prague airport a little earlier! We were soon joined by the other members of the party, John Timperley (Chief Engineer) Nic Raine (arranger/conductor) and Paul Bateman (arranger/conductor).

James has spent so much time in Prague that he has a good knowledge of the restaurants, and, in fact had already pre-booked all the evening meals! Two of the choices were in walking distance of our hotel and dinner followed a few minutes later at one of these. The food was excellent, though not always easy to digest due to much laughing as Nic Raine kept up a relentless succession of jokes, puns and banter - much of which was directed at John Timperley. Paul Bateman also had a few good stories (and the local accents to go with them) and Jason proved as unlikely an opera star as is imaginable, with some truly awful limericks and the most disgusting jokes! Incidentally, he revealed he spent six years in the fire-brigade before embarking on a professional career as a singer. He has a marvellous voice. Later on in the week I got to hear stuff like 'Oklahoma', 'You'll Never Walk Alone' and 'If I Loved You' - wonderful and very moving stuff.

Anyway, next morning we walked down the road to the studio for the second session. Nic Raine was first up with Raise The Titanic and James arranged a chair for me in the studio so I could alternate between there and the control booth. Being there for the recording of RTT was a never to be forgotten occasion. I could hardly believe I was sitting just a yard or so behind the violins during the live recordings - and I managed not to cough!

There's not much more I can say about the music itself as one will need to hear it to appreciate it. Suffice it to say I considered it was brilliantly played and sounded so authentic. The string sound in Prague is remarkable, and the woodwind pretty good, too, although the brass and especially rhythm section is never completely at home with 'Western-style' music. This later resulted in a few problems recording the Bond music. But it was explained to me that they would overdub any problem areas in London. Isn't technology wonderful?

During the afternoon, Nic finished off Raise The Titanic and made a start on the first Bond suite. The evening session was the first allocated to Paul Bateman & Jason Howard, and they got through a fair amount, despite the fact that Jason’s voice was a bit ‘gravelly’ – as he put it.

Friday was James Bond day. Having heard some of the ‘previously unreleased’ music via video so often recently, it was wonderful now hearing it played live in the studio. One has to remember that although nearly all this music is very familiar to most of us, as far as the Czech musicians are concerned, it is all still very new. In the circumstances, and with considerable assistance from Nic, they soon get into the swing of things. I am very new to orchestral rehearsals in the studio and was slightly taken aback by the tempo adopted by Nic Raine on occasions. For example, ‘From Russia With Love’, particularly the opening, was taken at a gallop, so much so that the rhythm section was a good yard behind the strings! "Surely they won’t be able to get that right?", I thought. But this is just Nic’s way of warming them up and making room for even more ‘takes’ per session, and after another couple of tries they were almost perfect. It’s an odd thing, but on occasions after an apparently successful take, I found myself wondering if they couldn’t get the opening just a little more together, when as if by magic Nic said as such to the orchestra! I should point out that both Nic and Paul Bateman used an interpreter for nearly all their instructions to the orchestra. The interpreter, a violinist herself, was really good at her job and very little time was lost because of this. Occasionally Nic would ask for a retake but mostly the decision would be made by producer James (following the music bar by bar) or by engineer John, who might have heard a noise from the studio or be unhappy with the miking of a particular instrument or section of the orchestra.

As I mentioned earlier, there were some problems with the rhythm section. The Prague studio isn’t especially big, and although it easily coped with the 75 or so musicians, it isn’t always possible to position the percussion and guitars to the best advantage. The cymbal player was moved upstage and backstage, the vibraphone player’s mike was moved closer, the guitarist was completely re-sited – all until John was satisfied. On one occasion the decision was made to ask the electric guitar player to remain silent during his piece, since he had brought the wrong guitar to the session! When they played the ‘spider’ music from Dr. No, with its final crash, crash crash, the orchestra fell about laughing! Must remember to tell Monty Norman!

John Timperley is an amazing character. This is his fortieth year in the business and he is now an independent engineer. He started his career at Chappells in 1960 and was given his first opportunity by legendary Robert Farnon. He also recalls working with John Barry and Ron Grainer around that time, ‘King’s Breakfast’ was one of the latter’s earliest films. He spent nine years at Chappells during which time he worked with all the great artists, before moving to work in France for several years. I was surprised to learn that Norman Newell recorded several EMI acts at Chappells during the sixties. I had assumed everything was done at Abbey Road. One year in the late seventies, he spent one year recording rock groups - a year which nearly finished him off, he claims! He and Nic Raine were absolutely scathing in their opinion of the musician’s union, in particularly holding Don Smith as being responsible for losing musicians so much work in England.

Back in the studio, it was strange to see the acoustic guitarist, Peter Binder, playing ‘Gypsy Camp’, the cue originally created by Vic Flick back in 1963. He managed pretty well even though he had to be asked to put on his headphones because his timing was slightly out. Incidentally, Peter is one of the few Czech musicians to have a smattering of English.

Geoff Leonard

Visiting Prague

Visiting Prague was once again a wonderful experience. And even though the days were almost exclusively taken up by the studio sessions, we still found time to visit some excellent restaurants in the evenings.

The visit began early for me as I needed to catch the 3.15 a.m. train from Bristol to Heathrow Airport (coach from Reading), hence I had no sleep either that night, or indeed very much the following night in the hotel. It’s an odd thing, as you would think that tiredness would automatically kick in, but it didn’t work for me. In fact, I never really slept well on any of the nights in Prague, nor even on my first night back in Bristol. But gradually I’m getting back into the normal pattern of things.

Anyway, there was no problem with the train and coach, though it was a little cold at 4.45 a.m. outside Reading station waiting for the driver to let us in! The coach was surprisingly full, but it did have to drop people off at all four Heathrow terminuses. On arrival at terminus 2, I had to collect my foreign currency, which turned out to be a right pain and took almost half an hour due to the incredible stupidity of the staff at Travel X. I moved down to check-in and soon spotted Rickie Clarke from Silva, who was to be our score reader during the sessions. He had arrived from the nearby hotel with Nic Raine who was now busy parking his car. Chief Engineer John ‘One Take’ Timperley soon appeared and when Nic joined us we queued for our boarding passes and checked-in our luggage. James Fitzpatrick had flown out the day before, incidentally.

The flight was uneventful and on time, and I had a few hours to relax before the first session began at 5 p.m. Unlike JT, who had to spend 6 hours setting up his equipment in the studio!

I was pleased to recognise many familiar faces amongst the orchestra and the first session began with ‘The Lion In Winter’. I thought at the time, and James confirmed later, that it’s always a nervous moment when they start. This was no exception and my heart sank a little, as they seemed ‘all over the place’ with certain sections of the orchestra playing at different tempos! But this was just a warming-up exercise, apparently. By the second or third attempt they sounded much more like it, and soon we were ready for the first recorded take. I think the orchestra numbered around 70 for the Barry sessions and they sounded terrific. Of course, for both ‘Lion’ and ‘Last Valley’, it’s difficult to judge how effective the recording has been, since the choir is missing and will be added later on in London. But everybody seemed highly satisfied with this first session, so this was a good omen.

The Last Valley was next up on the schedule and with the orchestra now fully in a ‘Barry’ mode, they sailed through it with aplomb and confidence and with the suite from Mary Queen of Scots also going smoothly, we began to get ahead of schedule. This was sure to prove useful when the orchestral had to tackle more complex material from Newman and Tiomkin later on.

My own day or days was Friday and Saturday with the recording of Robin & Marian. On the flight out I had mentioned to Nic that this year sees the 25th anniversary of the film, which is sure to prove a useful marketing tool for the CD. Once again, the orchestra proved more than equal to the task and despite a few retakes being necessary for ‘noise’ in the studio, the scheduled session for Sunday morning proved almost superfluous, there being just one cue left to record. By now we had been joined by Mark Ayres, who was having three of his compositions recorded by the COPP. One of these, ‘Meg Foster’, contained challenging variations in style and tempo – and the orchestra seemed to find this rather stimulating. They were smiling a lot, anyway.

The majority of Sunday and Monday were given over to recordings by Alfred Newman, Max Steiner and Dmitri Tiomkin, but there was also time for themes to Hannibal (Cassidy), Young Sherlock Holmes (Broughton) and Sunshine (Maurice Jarre). The latter required the presence of a Cimbalom. This was a special moment for me as I never previously seen one of John Barry’s favourite sixties instruments. In fact, I enjoyed Jarre’s composition very much, and it was this melody that remained in my head during the somewhat tedious plane journey home. I took some video film of many of the rehearsals for all the sessions, though annoyingly my Lion In Winter one has disappeared!

Newman’s Street Scene was a real treat both to hear and to see played. By now the orchestra had swelled to a 90-piece, and included five sax players! Nic took a lot of trouble with this piece and I think the end result justified him entirely. I have to say that it must have been a little out of the ordinary for this orchestra but they looked to be having a really good time. Other themes recorded included ‘Nevada Smith’, ‘20th Century Fox Fanfare’, ‘Captain From Castile’ (also wonderful), ‘Anastasia’, ‘Duel In The Sun’, ‘Bonanza’ & Gunfight At The O.K. Corral – another highlight.

I suppose it will be some time before I hear any of this music in the comfort of my own home, but at least I have the videos and some reasonable photos. I have to mention and pay tribute to the expertise of the entire production team which made things go so smoothly, led, of course, by James Fitzpatrick. He occasionally seemed to hear tiny little imperfections in the playing that I missed, necessitating another take, but as he said "You have to do these things properly"!

One amusing moment came when one of the percussion team, I think it was Tony, was asked to give us a little more from his cymbals. He replied that loud noises frightened him. And he had no answer when Nic asked him in that case why had he become a percussionist!

I mentioned the restaurants earlier. During one evening in one we were approached by an American gentleman who had heard us talking about music and wanted to know who we were and what we were recording. We said we were recording film music and his eyes seem to glaze over a little. We then gave a little more detail by mentioning Max Steiner, Alfred Newman, John Barry & Dmitri Tiomkin etc., but he still seemed somewhat disinterested. He said he was the principal clarinettist with the New York Philharmonic, and I suppose it's just possible he was not familiar with much film music - golden or silver age. His wife had a few words, too, and it turned out she is also a clarinettist.

A night or two afterwards in a different restaurant we were approached by another gentleman, this time from England, I think. He, too, had heard our musical discussion (we must have loud voices) and in particular caught a reference to an engineer named Keith Grant, who is quite well known around the London studio circuit and Olympic Sound in particular. He immediately adopted a sneering attitude when he made the assumption we were recording music in Prague 'on the cheap', but apart from saying he was a musician who had recorded with Grant "many times", he refused to identify himself. I didn't like him very much.

So, an enjoyable and successful trip. I wonder if there is any Barry music left to record now? Something will turn up by this time next year, I’m sure. In the meantime, I’m sure James & co. will be returning before then to finish off what didn’t quite fit into these sessions.

Geoff Leonard

The James Bond music

Geoff Leonard & Pete Walker

Tomorrow Never Dies, the eighteenth official James Bond film, opens around the world in December. David Arnold has written a marvellous score, his first of the series, which is already receiving rapturous reviews. Arnold is just the latest in a long line of talented composers who have left their mark on the series, but the overall musical style and format of a James Bond score was developed by John Barry. To date he has been responsible for eleven complete scores, and he had a significant hand in the theme for the very first, Dr. No, which was scored by Monty Norman.

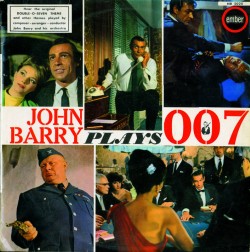

Barry’s involvement in the series began in July of 1962. In those days, he was still mainly involved in the pop music world as musical director for EMI Records in London, despite having already scored a few relatively low budget films. Monty Norman, a noted songwriter, had been commissioned to write the score for Dr. No, but with time running out had been unable to develop an exciting and dynamic theme. Barry and his band, The John Barry Seven, had, by that time, acquired a reputation in the UK, which probably explained why Barry’s name had entered a discussion over the problem with the music at a hastily convened meeting. He was contacted by Noel Rogers, the head of United Artists music publishing division, then invited to a Saturday morning meeting with Rogers and Monty Norman. From this point onwards, opinions differ on exactly what part Barry played in the composing of what is now universally known as ‘The James Bond Theme’.

Whereas both Norman & Barry remain equally convinced they wrote it without any help from the other, music editor Peter Hunt (who was arguably closest to the situation) believes that it was a joint effort, with Barry moulding Norman’s basic melody line into the classic arrangement we know today. What is certain is that after accepting the assignment, Barry had to work very fast. He recalls now that he was so keen to further his film career, he would ‘score anything that moved on celluloid’! In fact, he completed the theme without seeing even a rough-cut of the film, basing it on the style of Mancini's Peter Gunn and Nelson Riddle's Untouchables.

Whatever one makes of the writing controversy, one can’t deny that The James Bond Theme remains a classic record. When it was recorded at Abbey Road Studios, producer John Burgess remembers just how fastidious Barry was in arranging the orchestra prior to recording, giving special attention to the brass section in order to get the sound he wanted. This recording was so good that the Bond production team hastily inserted it, not only over the titles, but also throughout the movie, unbeknown to Barry, who only found this out after paying to see the film.

With Messrs Broccoli and Saltzman so obviously impressed with his rescue work on Dr No, he immediately came into the reckoning for the sequel, From Russia With Love. Barry recalls meeting Lotte Lenya, Ian Fleming and Robert Shaw at Pinewood, and then being flown out to Istanbul with Broccoli, Saltzman, Sean Connery and director Terence Young. During a conversation with John Williams, Mr Young looked back to those early days of the James Bond series. "John Barry came into our lives when we were making Dr No. We had someone else doing the music and although the score was all right, we didn't have anything exciting for the title music. I think it was someone at Chappell who said you must listen to him. He had a little band called The John Barry Seven and he came in and wrote this Bond theme.

Then, I don't know why, they were awfully wary about him. They thought he was too young and in-experienced in film music and I had a little bit to do with his finally doing From Russia with Love. Somebody wanted Lionel Bart to do the music. Lionel came into my life a few years earlier when I chose a song of his for a film I was making, Serious Charge. The song was called 'Living Doll' and of course is still around today. I said that if John Barry was in-experienced, then so was Lionel, and I think we owe it to John to give him a chance. Harry Saltzman, I think, was keen on Lionel Bart and I must say I was too, I liked him very much, but I couldn't see why they were doing John down because of his in-experience. If they had taken someone like Williamson who was one of the classical composers, it would have made more sense. Cubby Broccoli was on my side and in the end it was two to one - I think Cubby was the decider we should go with John. In the meantime, I think Harry had committed himself to Lionel Bart, and that's why Lionel wrote From Russia with Love, which was a charming song."

Still without a Bond theme of his own, Barry decided to introduce us to 007 as an alternative action theme, possibly not wishing to continually use The James Bond Theme, in view of Norman's writing credit. He also began his long tradition of making orchestral arrangements from the title song and reworking it into a love theme. The soundtrack album contained most of the important music from the film and also included a splendid track entitled The Golden Horn, which wasn't used in the film. Matt Monro was chosen to sing the theme and this was first heard briefly a few minutes into the film, as background radio music. Monro's recording is heard again though, in almost complete form, as the end credits roll. The highlights of the album included Girl Trouble, Leila Dances (though not the version heard in the film), 007 and Gypsy Camp. Many of these including excellent guitar work from Vic Flick, who was fast becoming a sought-after session player, following his decision to leave the John Barry Seven.

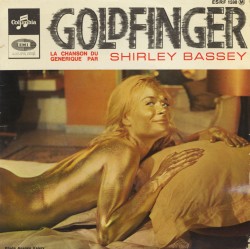

Goldfinger is without doubt Barry's favourite of all the Bond scores, and he has often stated how he believes he caught the mood just right. It contained the most internationally successful title song so far, sung by Shirley Bassey, despite only reaching number 21 during a nine-week stay on the UK best seller lists. It did, however, make the coveted number one position in Japan in June of 1965. Interestingly, Bassey's single featured a slightly different vocal to the soundtrack album version. Subtle differences can easily be detected in her phrasing of the words and also on the playout where she holds the note on "gold" far longer than on the album take.

Having been given the responsibility of writing the theme song for the first time, Barry invited Tony Newley and Leslie Bricusse to compose the lyrics. According to Bricusse, he and Newley had known Barry on a personal basis for some time, though they hadn't worked together professionally. Barry also frequented Bricusse's restaurant, The Pickwick Club, where along with his friends Michael Caine and Terence Stamp, he lunched every Friday. Moreover, he also shared the same divorce lawyer as Newley. According to Barry "Goldfinger was the craziest song ever. I went to Tony Newley to ask him to write the lyric. He said, "What the hell do I do with it?" I said "It's Mack TheKnife - a song about a villain. The end result worked just perfectly." In fact, Newley and co-writer Leslie Bricusse initially dumbfounded Barry after he played them the opening bars of Goldfinger, by singing the next line as "Wider than a mile" - a line from Mancini's Moon River!

Although sales of the soundtrack album were steady in the UK, they were absolutely sensational in America. There, Goldfinger succeeded in knocking the Beatles' A Hard Day's Night from the top of the album charts, and in winning John Barry his first gold disc for over a million dollars in sales. It sold over $2m worth in six months, was number one for three weeks and stayed high in the US charts for seventy weeks. The score also won a Grammy nomination. The US album contained less music than the UK release, omitting Golden Girl, Death of Tilley, The Laser Beam, and Pussy Galore's Flying Circus. However, unlike the UK release, it did contain the instrumental version of the main theme, which had been released as a single both in Britain and America. The CD re-issue disappointingly stuck to the original American format, but completists were able to pick up the missing tracks by purchasing the double CD: The Best Of James Bond - 30th Anniversary.

For Thunderball, the fourth film in the Bond series, the producers realised from the outset that Goldfinger would be a difficult act to follow. They had already started introducing more and more gimmicks into the films and for this outing they felt it a good idea to drop the normal title song, (Thunderball was thought to be lyrically difficult in any case). They therefore decided to use the name by which Bond had become known in Italy and Japan - Mr Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Accordingly, Barry based the entire score around this title song which had lyrics written solely by Leslie Bricusse (Newley was working in America at the time). The Bond team had even chosen Dionne Warwick as singer, after Shirley Bassey's original version had failed to impress. Barry takes up the story: "Dionne's was a marvellous song and she did a great arrangement for it. It was a really strange song. I had about twelve cowbells on it with different rhythms, along with a large orchestra, and thought it a very original piece. Then, at the last minute they got cold feet and decided to have a song called 'Thunderball'." The official reason for this sudden change of mind revolved around the possible controversy surrounding the sexually risqué song title in conservative America. More pertinent, possibly, was an alleged court action from Miss Bassey herself following her replacement by Warwick. Obviously if the song wasn't used at all, there could be no case to answer!

Whatever the reason, it led to Barry's long partnership with Don Black, who took over as lyricist as a result of Bricusse’s inaccessibility through working in America. When director Terence Young heard Thunderball for the first time, he said it sounded like 'Thunderfinger'. Barry's laughing rejoinder was to the effect that "I gave them what they wanted." Incidentally, both unused vocals are on the double CD: The Best Of James Bond - 30th Anniversary, along with a lengthy suite of music also excluded from the soundtrack album.

On You Only Live Twice, Barry teamed up again with Leslie Bricusse to produce a beautiful song, sung over the opening credits by Nancy Sinatra. However, the appearance on the American issued Bond 30th Anniversary double CD, of a completely different song entitled You Only Live Twice - demo, raised a few eyebrows. The vocal is by an unnamed female session singer with Barry and Bricusse credited as writers. Leslie Bricusse confirmed that this was their first attempt at the title song, which they eventually discarded.

The singer turned out to be Julie Rogers, best known for her hit, The Wedding. Julie was quick to point out that her recording was not intended for demo purposes. On the contrary, she was actually chosen to sing the new Bond title theme on the strength of her aforementioned hit. As she rightly points out, "Successful TV and recording artists do not record demos!" Her song was recorded at CTS studios, Bayswater with Barry himself conducting a sixty-piece orchestra. Julie believes that only late pressure from the producers resulted in Nancy Sinatra eventually taking over as vocalist. Although Sinatra did indeed get the job, she was by no means second choice either. According to Bricusse, Barry had already lined up Aretha Franklin on the eve of her signing for Atlantic Records. However, the producers were insistent on using Nancy Sinatra who had just topped the charts with 'These Boots Are Made For Walkin'. Barry recently revealed that it took twenty takes before he was completely satisfied with Sinatra’s performance, due apparently to her nervousness in front of the microphone.

Unusually, Barry composed an instrumental to open On Her Majesty's Secret Service, probably as a means of resolving the problem of fitting a suitable lyric around what is a rather cumbersome film title. Although Barry's most recent ‘Bond Theme’ collaborator, Leslie Bricusse, was convinced of his ability to write a suitable lyric, the decision to opt for an instrumental proved the right one.

The film's screenplay was closely based on Ian Fleming's original story relating Bond's romantic entanglement and eventual marriage. To compliment the courtship scenes Barry wrote a beautifully haunting melody with the working title, We Have All The Time In The World, directly lifted from one of Fleming's own lines from the book. This combination of music and title provided Hal David with the skeletal framework around which a lyric could be constructed. Although he had only just left hospital after a long illness, Louis Armstrong was considered the ideal person to sing the finished song, on John Barry's own suggestion. "There was a line in the script, almost the last line – ‘We have all the time in the world’, as his wife gets killed, which was also in Fleming's original novel, and I liked that as a title very much. Now I'd always liked Walter Huston singing 'September Song' in the film September Affair, where as an older character he sang about his life in a kind of reflective vein. So, I suggested to Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman that Louis Armstrong would be ideal to sing our song in this fashion." Tragically, it was to be his last recording before his untimely death. "He was the sweetest man alive but having been laid up for over a year, he had no energy left. He couldn't even play his trumpet and still he summoned the energy to sing our song – if only a verse at a time. Afterwards, we were able to edit everything together to produce the marvellous recording you hear today. At the end of the recording session in New York City he came up to me and said ‘thank you for this job’. I couldn’t believe it, he was my hero and he was thanking me!"

The Armstrong song was a huge hit in Italy, thanks fortuitously, according to Barry, to a DJ based in Rome, who played the record virtually non-stop for an entire evening. Such saturation coverage sent it hurtling to number one, where it remained for nine months!!! Barry commented: "Italy was the only country where we had any success with the song. It was a very heavy song so we couldn't use it as the title track. It was buried inside the film and that probably hurt its chances of success. The song itself was written for a very emotional moment. I had pictured Sean Connery in the role of Bond when Hal and I first wrote the lyrics. If it had been Sean who married Diana Rigg and then lost her to Blofeld, then the song would have been beautiful and highly appropriate. Having Sean Connery and Diana Rigg together in the last scene would have really created a bombshell of a moment. With all due respect to the inexperience of George Lazenby, he couldn't have created a boiled egg in that last scene! He turned up for one of the recording sessions and seemed surprised that my music worked for a particular scene. He congratulated me as though he was doing me the biggest favour I had ever had – it was as though he hadn’t realised I wrote film music for a living!" Lazenby’s other ‘contribution’ towards the music was to suggest ‘Blood Sweat & Tears’ to perform ‘We Have All The Time In The World’, though he later admitted he was wrong.

The failure of Armstrong's song to dent any chart outside Italy, was remedied in England almost 25 years later after it was used for a Guinness television commercial. EMI saw fit to issue the song, as a result of public demand, at which point it climbed to number three in the charts.

Actor Charles Gray met an early death in You Only Live Twice in the guise of Dikko Henderson, Bond's initial contact in Japan, but was reincarnated in the form of Ernst Stavro Blofeld for Diamonds Are Forever, the seventh film of the series! Sean Connery was persuaded back for a final appearance as James Bond, after United Artists promised to back two of his own future film projects, plus the payment of an enormous fee for his services. John Barry needed no such encouragement to work on his own seventh Bond score, although afterwards he was reportedly furious with co-producer Harry Saltzman's low opinion of his theme song, performed by Shirley Bassey in her own inimitable style. According to Don Black, Saltzman thought that the lyric "hold one up and then caress it, touch it, stroke it and undress it" was "dirty". Apparently, after questioning Saltzman's competence to make a critical analysis of the song, Barry virtually threw him out of his Cadogan Square apartment. His anger with Saltzman even influenced his decision not to score Live & Let Die, the next film in the series, but fortunately few shared the producer’s opinion, since the song went on to win an Ivor Novello Award for Barry and Black. As usual, Barry produced some memorable action cues, yet they failed to find their way onto the soundtrack album, dominated as it was by those cues that reflected Las Vegas mood music.

By 1973, Barry was heavily involved with Don Black in the writing of the musical, ‘Billy’. He had agreed to give this project priority over any film music assignments and his disagreement with Saltzman hardly helped matters. Filming of Live And Let Die (Roger Moore’s debut in the title role) began in the Bahamas with no decision made as to who would score the film; that was until Saltzman received an unsolicited title theme song tape demo from Paul McCartney - and they weren't going to turn THAT down! After embarrassingly suggesting a female singer to perform the song, the producers eventually agreed to McCartney tackling it himself, with friend and mentor George Martin commissioned to write the score.

After turning down many other film-scoring opportunities due to his involvement with 'Billy', Barry was now faced with a particularly heavy schedule, and may not have been able to devote sufficient time to Man With The Golden Gun (1974). Apparently, he wrote the complete score in just three weeks, and was, according to Don Black, dissatisfied with the title song they wrote together. Vocalist Lulu was not at her best on the recording session, either, due to a sore throat. Not surprisingly, the resultant single sold very poorly - one of the few Bond theme vocals to miss the charts completely. Even though the soundtrack was a reasonable representation of the film score, Barry appeared to be signalling a certain boredom with the JB formula.

In fact, soon afterwards, Barry left England to initially live in Majorca, before moving permanently to America. He was badly missed on 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me, although his replacement, Marvin Hamlisch did write an excellent theme song - Nobody Does It Better (with lyricist Carol Bayer Sager). Sung by Carly Simon, it was deservedly nominated for an Oscar. However the rest of his score didn't really match the requirements of a 1970s Bond film, in spite of receiving an Oscar nomination - something even the classic Barry scores failed to achieve. The score has its good moments, but ‘Bond 77’ and ‘Ride to Atlantis’ both have a very dated 70s sound.

A dispute with the Inland Revenue almost deprived the Bond camp of Barry’s services for Moonraker (1979), until it was decided to partially shoot in France. As a consequence, recording at the Davout Studios, Paris became a practical necessity, enabling Barry to avoid entering the UK. Now resident in America, Barry was reunited with lyricist Hal David to write a title song with Johnny Mathis in mind. Unfortunately, his vocal failed to work in the way it was envisaged. Barry was reflecting on this dilemma one day in a Beverly Hills hotel, when Shirley Bassey happened to walk in. Eureka! Problem solved. Moonraker became another excellent, haunting song, performed admirably by Bassey in her most sensual fashion, and it was a major surprise when the single failed to register in the charts. A much faster, almost disco-oriented rendition accompanied the end credits. Both versions made up the aforementioned single, although in Britain, the label credits were reversed - doubtless causing considerable initial confusion to radio presenters!

It was John Barry himself who persuaded the producers to appoint Bill Conti as his replacement for 1981’s For Your Eyes Only, when he found himself unavailable because of the aforementioned tax problems. Conti’s main worry centred around the theme song. After scrapping his original version on the advice of a friend, he combined with lyricist Michael Leeson to create an Oscar-nominated title song, performed during the opening credits in vision by Sheena Easton – the only occasion on which this has happened during the series. Unfortunately, the rest of Conti’s score was dominated by the then very fashionable disco beat, which has since dated the score rather badly.

In 1983, Barry decided the time was right to work again England. In order to do so, he not only chose to settle an outstanding tax bill, but also bought a property to use as a London base. He returned to the same Cadogan Square in which he resided during the sixties, and where he had written so many of his successful scores. John Glen had started his long run as Bond director with For Your Eyes Only, but Octopussy was the first time he and Barry had worked together as director and composer. However, as he recently told JohnWilliams, he had known Barry from many years prior to this: "In the fifties when I was a national serviceman stationed on the East Coast of England, playing at the local town hall was the John Barry Seven. Later our paths were to cross again. As a film editor I was associated with John on several movies. I remember On Her Majesty's Secret Service particularly well, as this was my introduction to the 'big time'. John wrote a particularly memorable score for the ski chase sequence using a moog synthesiser, at that time a novel instrument. He was always searching for that unique sound, sometimes new and sometimes from an ethnic source. Of course, the search for the broken guitar, which gave the James Bond Theme in Dr No such a great quality, is legendary in Bond circles. Never to be repeated as Vic Flick apparently threw it away. What else would a great guitarist do with a cracked guitar? John was lost to the Bond films for a number of years and I was fortunate that he was able to return for three of the films I directed: Octopussy, A View to A Kill and the Living Daylights. As a director what can one say to John Barry about the music for a Bond film? His contribution to the success of the series has been enormous. His needs were always very simple. A piano, a Moviola and not very much time. Six weeks was about as long as he got. Bond films always had a pressing release date and then there was always the title song."

On the subject of the Bond title song, the majority have eponymous themes, but there are occasions when this is not possible - Octopussy, an obvious example. When Barry and his new lyricist Tim Rice began working on the theme, Barry set Rice an unusual task. In order to satisfy the producers, he asked Rice to write half a dozen lyrics, on the basis that they would like at least one of them! Rita Coolidge was the surprise choice to perform All Time High in view of her low profile at the time. However, the producers were convinced that here was a potential ‘standard’, requiring someone of the class and easy-listening singing style of Coolidge to perform it. In the event, their conviction proved accurate. After reaching only number 75 in the UK charts it has since become something of an evergreen. The original soundtrack CD was issued on A & M but quickly withdrawn due to a printing error. Bond collectors have been known to pay hundreds of pounds for a copy. Thankfully, Rykodisc have recently re-issued it, complete with detailed booklet notes and photographs from the film.

John Taylor, of Duran Duran, a keen Bond / Barry fan, had cheekily suggested to Cubby Broccoli that the group would be ideal to write and sing the theme song for A View To A Kill. However, when they got the job, their initial reaction was one of fear! Of course, this was one offer they simply couldn't refuse, particularly with Barry apparently keen on working with them. Lead singer Simon Le Bon: "He didn't really come up with any of the basic musical ideas. He heard what we came up with and he put them into an order. And that's why it happened so quickly because he was able to separate the good ideas from the bad ones, and he arranged them. He has a great way of working brilliant chord arrangements. He was working with us as virtually a sixth member of the group, but not really getting on our backs at all."

Barry was amused by John Taylor's knowledge of his work: "He knows more about stuff I've done than I know myself. He'd pick out a scene from an old movie, and I mean old, and talk about it like I'm supposed to remember it as if it were yesterday!" Following the departure of CTS's resident engineer John Richards to America, A View To A Kill was the first occasion on which Dick Lewzey had been entirely responsible for the mixing. He was also responsible for recommending the orchestrator Nicholas Raine to Barry. The two have worked together on many occasions since. ‘A View to a Kill’ remains the only Bond title song ever to make number one in America (it reached no. 2 in Britain).

A View To A Kill marked the end of Roger Moore’s long run in the title role and his successor, Timothy Dalton, made his debut in The Living Daylights. For the first time in the series, Barry wrote a separate theme for the end titles sequence. He commented: "I thought it would be lovely at the end of the movie, instead of going back to the main title song, to have a love ballad which is the love theme that I used throughout the four or five love scenes in the picture." This theme was sung by Chrissie Hynde of The Pretenders, who also wrote the words. Another Barry / Hynde song was included within the body of the film, and both of them were recorded with synthesised backing at Paradise Studios in Chiswick, London.

Barry started work on The Living Daylights in May 1987 by making full use of a 24-track digital technology available at CTS, Wembley. Both Barry and Lewzey were impressed with this format with Barry recalling how he recorded the very first digital film soundtrack, Disney's The Black Hole. "I love digital - it's just that much better than analogue, everything major I've done has been onto digital." A majority of the score used synthesised rhythm tracks and Barry added: "I wanted to put in these tracks and they really cut through. We've used them on about eight pieces and when we got them mixed in with the orchestra it sounded really terrific with a lot of energy and impact - a slight freshness and a more up-to-date sound."

Barry wrote some 57 minutes of music for this film in just four weeks! Band tracks were laid down at Maison Rouge Studios in South London, overlaid orchestrally at CTS, and finally remixed at the Power Station in New York. John Barry was reportedly unhappy with A-ha’s approach towards their performance of the main theme, comparing the experience as "Like playing ping-pong with four balls."

He was even less pleased with their attitude following completion of the theme song, when they refused to have anything further to do with the film. There was undoubtedly a certain amount of creative friction - "The old meeting the new", said Aha, who had been recommended to Michael G. Wilson by Ray Still, who had been involved with the Duran Duran project, and was then director of the US label, Warner Brothers Records. Pal Waaktaar, leader of the group, liked the idea of working with Barry but afterwards described it as "a strange experience - the song is not really a favourite in its current form!"

Illness prevented Barry from returning to score Licence To Kill, in 1989, even though production was delayed in the hope he would recover in time. Vic Flick did return, however, to play guitar on Michael Kamen’s sessions. Originally, Flick and Eric Clapton were to have performed the title theme as an instrumental but the producers reneged on the idea - hence Gladys Knight, and what was to lead to a worrying trend in demarcating song and score chores. Kamen, recruited to write the score following a string of successful action assignments, provided an interesting blend of traditional elements and a new approach with Latin guitar. The new tradition of having a different end-titles song continued via Patti LaBelle with ‘If You Asked Me To’, but this wasn’t written by Kamen, either.

Legal wrangles prevented any further James Bond adventures until 1995’s GoldenEye, by which time Timothy Dalton had decided it was time for him to hang up the tuxedo and revolver. Barry, too, apparently decided enough was enough, and although courted at length by the producers, claimed he was too busy on other projects to be able to give the film the time and attention it deserved. Director Martin Campbell was keen to use Eric Serra, famous for his electronic, synthesiser scores for Luc Besson’s films. Barry thought that a change in direction was certainly one option, especially after a six-year gap, but warned it might prove difficult to move away from a long established format. Words that were to prove only too true when Serra’s score was heard. In truth, it wasn’t a bad score as such, but didn’t seem appropriate for a Bond film. It is rumoured that had the producers more time, they would have rejected the score completely, but as it was they did insist on replacing the music for a key tank chase sequence with an orchestrally scored version of the James Bond theme. This was arranged by John Altman, Serra’s conductor for the sessions, as Serra was of the opinion that what he had written should be left in the film! Only the title song, written by Bono and The Edge and sung by Tina Turner can be said to be satisfactory, but even that is very derivative of the Barry/Bassey approach. Serra also made an error by electing to sing his own end-titles song, which was not entirely suitable for that purpose.

This leads us back to the current score to Tomorrow Never Dies. David Arnold has written a traditional Bond score, cleverly utilising elements of previous Barry scores while simultaneously updating it and imposing his own personality. He has also composed an excellent song, ‘Surrender’, sung by k d lang, with lyrics by Don Black, which is disappointingly relegated to the end titles sequence. Like Barry before him, Arnold has incorporated parts of his theme into other cues in the score, but this cannot be said of the main title song by Sheryl Crow. Fans of techno are rewarded by a version of The James Bond Theme by Moby, and it is encouraging to note that the overall length of the album is, like GoldenEye before it, well over fifty minutes. Now that the musical baton has been successfully passed onto a self-confessed Barry connoisseur, one can only hope that the true spirit of Barry’s original blueprint will live on into the millennium. Tomorrow, as they say, never dies.

Geoff Leonard & Pete Walker

This was a day I shall never forget

(November 1998)

John Barry’s music has been a big influence on my life ever since I was a teenager. I can’t remember the first occasion on which I became aware of his music, but it was probably through watching the Saturday night BBC TV programme, Juke Box Jury, which used his ‘Hit & Miss’ composition as the signature tune. Looking back, the programme seemed to be on every Saturday night throughout the sixties, but I suppose it must have rested during the summer months of each year! There was also a Sunday morning BBC radio programme entitled Easy Beat, for which he also wrote the theme. It was required listening before the walk to catch the 11 o’clock service at our local church, which, incidentally was inevitably followed by dinner of roast beef, pork or lamb. Poultry was strictly only for Easter or Christmas. For the first few months of Easy Beat, The John Barry Seven were resident band, but I think they had been replaced by Bert Weedon by the time I tuned in.

The John Barry Seven vied with The Shadows for the position of Britain’s top small band. Although I was keen on The Shadows, too, there was some indefinable quality about the John Barry sound which made me want to start collecting his recordings from then onwards. Indeed, ‘Walk Don’t Run’ was the first 45 I ever bought, albeit a second-hand copy!! I think I paid two shillings for it (full priced singles were about six shillings and eight pence) from a shop in Gloucester Road, Bristol called Wookey & Jones. They also sold second-hand TV sets, as I recall. I must have listened to that record hundreds of times in the attic of our family home in Bristol - the only place I was allowed to play music at a decent volume level - marvelling at Vic Flick’s guitar solo which was so different from the other versions released at the time. He has since told me that EMI released the take on which he felt the guitar tremelo arm effect was slightly over done, and out of tune – which might explain my fascination! And the sound coming from those big old-fashioned speakers has never been matched. As I type this out I can almost hear that opening drum sound from Walk Don’t Run and smell the rather musty scent of the attic, prior to it being modernised. Other singles I bought around that time were Roy Orbison’s ‘Only The Lonely’ and Helen Shapiro’s ‘Don’t Treat Me Like A Child’. The latter being the first full-priced single I ever bought.

I was the second eldest in a family of three boys and a girl, and in the late fifties/early sixties in Bristol, we led rather a sheltered life. My mother wasn’t too keen on ‘pop’ music, she didn’t like me listening to Radio Luxembourg (the only radio station playing proper pop music back then), and as I have no memory of Drumbeat - Barry’s first big TV success in 1959, I can only assume the programme was turned off during that summer. Bear in mind that BBC was the only channel we could then receive. ITV had started a few years previously but you had to purchase a new TV set to be able to receive it. I think I remember her expressing outrage at the general appearance of one Adam Faith, and as he was a regular on Drumbeat, that might explain it.

I really want to be able to say I saw the JB7 on Drumbeat, but in all honesty I cannot recall it. Even if I saw part of a show, as seems likely seeing it ran for 22 weeks, at eleven years old I probably wouldn’t have been aware of the band and Barry. Eleven was a lot younger in terms of appreciating pop music in those days. I’ve even examined the details of a Saturday’s evening’s BBC TV output from that period, and gallingly I can definitely remember watching the closing overs of England v. India at cricket which directly preceded Drumbeat. As I said, maybe Mum or Dad turned off or maybe I rushed out to the local park to try and copy my heroes? I shall never know! I do remember seeing them appear in a TV play called Girl On A Roof. Well, to be fair, I remember watching the play. A girl threatened to jump unless her pop-star hero (played by Ray Brooks) agreed to meet her or maybe even marry her. He eventually did but destroyed her dreams by proving how appalling he really was by singing unaccompanied very loudly (and badly) right in her face ‘I Want You Baby’, which he clearly didn’t. And neither did she after that! I remember hearing the JB7’s music playing while they were on-stage and the action was off-stage, but not much about them being on camera. Well, it was 38 years ago!

As I grew older, I continued to collect John Barry records, which had become more and more experimental - particular the ‘B’ sides of his singles. The famous guitar sound was now beginning to share top billing with strings. The very last track on his first studio album, Stringbeat, was entitled ‘The Challenge’, and some critics felt this was a theme written for a film yet to be made. It was in such contrast to compositions such as ‘Hit & Miss’, from only a year or so before, that even at my tender age I could tell a change was on the way. I came across his soundtrack to Beat Girl, again, in a second-hand shop. This had been an X-certificate (over 18 only) film so it wasn’t so surprising that I’d missed both the film and the album when they were originally released in 1960. This, too, contained tracks unlike anything I’d heard before, in particular jazz-styled numbers like ‘Time Out’ and ‘The Off Beat’. I like to think I bought all his records in those early days, mostly as soon as they come out. Some I definitely remember buying new, like ‘Starfire’, ‘The Menace’ and, of course, ‘The James Bond Theme’. I also bought an e.p. called ‘Theme Successes’ new for about 11 shillings and 6 pence, but ‘The John Barry Sound’ e.p. cost five shillings second-hand. I remind myself that before I got a regular paper-round in about 1962, pocket-money was one shilling a week which eventually rose to two and six. So the buying of new records was an absolute luxury.

Indeed, Stringbeat, my first LP, was a Xmas present in 1962 and the following year came the soundtrack album to From Russia With Love - Barry’s first real dramatic film score. I must have bored the entire family and guests almost to death by insisting on playing it repeatedly downstairs during the festivities. I was allowed down from the attic because film music seemed a mite more respectable!

In 1963, Barry signed for Ember Records. As a small label, their distribution was poor and I was fortunate that a new record shop opened near me, with a helpful owner. The shop was called 'Stephen Francis Records', even though the owner was called something quite different. He got me all the early Ember singles like 'Fancy Dance', 'Zulu Stamp' and 'Elizabeth', before he was forced to close down through lack of business!

Barry's Bond and 'Elizabeth Taylor In London' albums succeeded not only on getting me hooked on film music, but also on the cinema in general. The sixties was a great time for cinema-going in Britain and I saw all the major films - some of them more than once. However, not all Barry’s scores were for major films. Consequently, unlike his ‘pop’ days with EMI, I didn’t buy all his recorded output simply because I didn’t know about the film or the album. Albums like KingRat, Four In The Morning and Boom! come to mind. Man In The Middle was slightly different. I was working by then and ordered the album especially from a shop in Park Row, Bristol. When it finally came into stock I couldn’t afford to buy it. I was earning only about £7.70 a week, so £1.75 was a large chunk to find. Some weeks later I thought it was safe to return to the shop without being recognised and the LP was in the racks. However, although I had the money I was mortified to see on the cover: ‘Music By Lionel Bart’. Though a thorough examination of the back of the sleeve would have revealed that Barry did write a few tracks, I left it. And there it stayed for a few more months – if not years. I regretted this incident when I eventually bought the album in the eighties for around £15!

And there were albums which weren’t released in this country - I had no idea how to obtain these. Bear in mind that back in those days there were no specialist film music magazines that I was aware of and certainly no Internet! But the albums continued to surface and I bought many more than I missed. And, nearly always brand-new. Goldfinger, Ipcress File, The Knack, Zulu, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice and O.H.M.S.S., Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland - I recall buying as if it were yesterday. And where!

Then there were the concerts. I’ve already said I was living in Bristol back in the early sixties, and apart from a brief period away, I have lived here ever since. Nowadays it is relatively easy to find out about London concerts of film music. There are friends with similar interests to tip you off, adverts in film music magazines, the Internet and quite often appearances by the composer/conductor concerned on radio and TV programmes. But John Barry’s first film music concert in 1972 had taken place at the Royal Albert Hall before I was aware of it. Indeed, the first I knew about it was when he appeared on BBC TV in a special about his music, introduced by Michael Parkinson, when he conducted the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in a selection of music taken from that concert. At the Royal Albert Hall he had conducted the second half of the concert after Miklos Rozsa had occupied the podium for the first half – what an occasion that must have been! The following year, Barry was back again, with Muir Mathieson in tandem. This time it was several years before I found out about it.

But in the mid-seventies, Barry moved to America to live and the word was that he would not be returning, due mainly to various tax problems. UK-released albums seemed to dry up a little and it was a long time before I bought another one. Man With The Golden Gun was probably the last one I was aware of until Moonraker. I had no knowledge of scores such as The Deep, King Kong or Billy – it still puzzles me that a musical could run for over 2 years on the London stage without my knowledge! Maybe London was a ‘bridge too far’ in those days?

A few months working in London at the end of the seventies proved a good move for me. My brother was working there as a sound designer for the RSC and he told me where I could find rare soundtracks. 58 Dean Street & Dress Circle were his tips, and what gems I found there! I virtually filled all the gaps in my Barry album collection, including some from films of which I had never heard, like Starcrash, Petulia, The Last Valley, The Dove, Robin & Marian – the list was endless. And they weren’t cheap, either!

I was resigned to never seeing Barry perform in public, but for some unaccountable reason I did think it would be rather a good idea to write a book about his life in music. I’ve no idea why I had this thought. I had not written more than the odd letter since leaving school in the sixties, and even back then, essays were not my strongest point. To make matters worse, since his move from England there was very little information available about him in newspapers or magazines, and a Leeds-based fan club appeared to have folded. But I persevered and started to seriously research the book around the mid-eighties. I got some help from his ex-guitarist, Vic Flick, as well as two fellow Barry fans, Pete Walker & Gareth Bramley, whom I contacted via Record Collector magazine. From then onwards the book has been aborted, re-started and shelved again on many occasions, mainly due to the absence of a willing publisher, but also, it has to be admitted, due to a complete lack of interest from Barry himself. I had spoken to him on several occasions from the early nineties onwards but he seemed really only interested in the future. But in late 1997, Gareth, Pete and I decided we must go ahead and finish the book anyway, and were fortunate enough to find a sympathetic Bristol publisher, Sansom & Company. Gareth agreed to fund the book and a long-held ambition was finally realised in November, 1998, with the publication of John Barry – A Life In Music.

During quite a lengthy interview with Barry for Music From The Movies a few years ago, I had broached the subject of concerts. He made it clear that if he could get an orchestra he was familiar with, (the RPO was suggested) and the rehearsal time he considered necessary, he would be happy to perform. But subsequent comments from him gave the distinct impression that the thought of performing again in public filled him with dread. So, when film music writer Paul Tonks told me early in 1998 that Barry had agreed to give a concert at the Royal Albert Hall, I wasn’t entirely convinced this would ever happen! As it turned out, it was a day I (and I suspect Pete & Gareth) will never forget.

Pete and I had written the programme notes – at very short notice, I must emphasise – so we already knew what was likely to be played. I was both surprised and delighted to see that we were sitting in seats just one row from the very front and almost directly underneath the conductor's podium. Bear in mind we were so close, we couldn't see anybody walking on until they got right up to the podium. So I heard this great shout and chorus of approval and waited for the first glimpse of Barry. But it was Michael Caine! He got virtually a standing ovation himself! I guess he is still one of the most popular English actors around. He introduced Barry by re-telling the true story of how he kept him awake during the composing of ‘Goldfinger’, when he was a temporary guest at Barry’s Cadogan Square apartment. He embellished and extended it somewhat (a little inaccurately) and also delivered it quite slowly and deliberately – he knew he had us in the palm of his hand! I think it was almost 8.15 by the time Barry arrived on stage to thunderous applause, looking very nervous. He was visibly moved by the occasion - very moist-eyed - and said a few words in response to Caine, adding it was appropriate to start with Goldfinger and said, "Let's have some fun." And we were away.

For me, the undoubted highlight of this half was The Persuaders. To my great surprise, Barry & the orchestra performed it just as the original single was done, albeit presumably with a synth providing the sound of the cimbalom or whatever it is. But also outstanding was Midnight Cowboy, featuring Tommy Morgan on harmonica and Dawn Attack - from Dances with Wolves. Just a little different and even more exciting than the OST version. I also really enjoyed Moviola, even though Barry felt it was necessary to mention the Streisand business again! The first half lasted around 65 minutes and with a twenty-minute interval, the second half didn't start before 9.45. Clearly the expected 10.30 finish was way out of line!

Caine reappeared again at the beginning of the second half to present Barry with a replica of a BFI plaque which will go on the wall of the house where he was born in York. This added yet more time onto the half. Barry didn't introduce or back-announce everything. In the first half he commented on The Persuaders, Midnight Cowboy (partially to introduce Tommy Morgan), Amy Foster (to publicise the film) and Dances With Wolves. In this half, he introduced the saxophonist, David White, who was brilliant on Body Heat. Chaplin was extended to include Smile, and he then announced Space March as one of his most requested cues. This went down a storm! Then came Ipcress File and The Knack. This was another treat as both were performed in traditional style. The

Cimbalom (Synth?) sounded a little unsure of itself at first, but soon got into its stride. It was a wonderful moment. The Knack was simply terrific. A choir was sampled by the synths, presumably, and it was obvious the orchestra were enjoying this one! It proved exceptionally popular with the audience and Barry was seen to shake his head almost in disbelief at the ovation. "Very definitely a sixties sound," he commented. Obviously the Beyondness Suite was well-performed as the orchestra was most familiar with it. Barry pointed out 'Kissably Close', billed in the programme, was replaced by 'Heartlands'.

Finally, he introduced The Bond suite by commenting on the wonderful lyricists he worked with - "Don Black, Hal David, Tim Rice, Lionel Bart. Uh, Duran Duran, a-ha - is it any wonder I left?"!!! The suite was absolutely fantastic! The Bond Theme and OHMSS were the highlights for me. Brilliantly played. He left the stage to rapturous applause and returned to encore The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair. Despite a standing ovation, he didn't come back again and possibly there was nothing left to play, or no time to play it.

It was now around 11.15 - Pete would miss his last coach! And if I went to the Barry reception I would too. Well, of course I was going anyway, with Paul Tonks & Gareth Bramley. They wouldn't let Pete in without an invitation - of course, with his coach journey already booked, we hadn't thought he was going to be available for the reception - and we couldn't find any Decca officials within. I found out later that Pete had found an official outside the room, and told her that he had co-written the programme notes but she seemed to think Gareth was the co-writer and was already in and still wouldn't let him in. A great shame. Anyway, inside it was a heaving mass of people (not quite literally!). I couldn't believe the number of people there! I spotted Michael Caine and his wife just inside the door but they made a very quick exit, as did Don Black. Michael Winner was there, as was Gloria Hunniford and the DJ and writer Paul Gambaccini. Later I saw Basil Poledouris with Barry. I was introduced to Nick Redman, Jon Burlingame and Marilee Bradford, and also Richard Kraft - Barry's agent. A real thrill for me. I’m sure there were other personalities there, too, but I either didn’t recognise them or missed them in the initial crush. Barry himself was there with his wife, Laurie but was surrounded by people getting him to sign programmes. Eventually I took Gareth over there, introduced myself and asked him to sign my invitation card. He seemed pleased to see me and I think he remembered who I was. He sounded a little slurred - several glasses of Champagne, I guess! I told him how good the concert had been and he agreed! He thought there would be more at some stage in the future.

We left right at the end and wandered around London trying to find a decent restaurant open. This was now after 2 a.m.! We couldn't. We settled for a Burger place in Leicester Square in the end, and after Gareth went back to his hotel around 3.30, I spent the rest of the night/morning with Paul while we waited for our respective trains home. I’m hoping to get some sleep very soon, but as I said at the outset – it was a day I shall never forget, and who’s worried about missing a few hours' sleep?

A few days later at the HMV Signing

I'd arranged to attend the JB signing with Gareth, after we'd visited a few other places in town. We arrived at HMV at about ten minutes before the signing was due to commence. To my horror, there was a queue which stretched around the shop controlled by stewards and crash barriers. I had imagined him sitting behind a desk downstairs in the soundtrack department, chatting amiably to the occasional punter after a signature. No! HMV had set up a kind of stage on the main ground floor. There was a giant screen showing footage from Raise The Titanic and when that finished they played music from The Beyondness Of Things. So this could be heard throughout the ground floor - a floor which usually shakes to the latest dance or rock music! We decided to hang around for a while to see if rapid progress was made. Just after 5.30, some chap came on the PA and asked to give a big welcome to the one and only John Barry. To the sounds of 'Give Me A Smile', the man strode across the floor and up onto the temporary stage. It was like watching a Conservative politician entering the stage of his party conference while being cheered by his supporters.

Barry then took the microphone and made a little welcoming speech, thanking us all for turning up on such a miserable day (it had been raining an awful lot). He hoped we would all have short names like Ron, Eric and Bill. He didn't want any Alexanders, or Von Ryan Defreitases! He looked forward to meeting us ALL! The MC then said Mr Barry had consented to answer a few questions. He had some himself and would then put some from the floor which he had collected earlier. I got the impression some people had been there for hours! Anyway, suffice it to say, the most interesting question was about the concert. JB admitted to being terrified for the first ten minutes and for the previous 3 days! He considered throwing himself under a bus and seriously wondered about turning up at all (I worried about that!). But after that initial feeling of panic, something wonderful happened and the music and orchestra took over. He thought it was a very special evening. The MC reminded him and us that the concert could have been sold out on two more days. Barry said he was having discussions about doing another 3 days at the RAH (didn't say when) and then taking the orchestra to selected UK cities like Manchester & Birmingham "Where they have these wonderful new symphony halls". He said money wasn't an issue. He would do it for the sheer joy and as long as they broke even he didn't mind. But he insists on doing it with a full orchestra, not 40 players. Otherwise the fun goes out of it.

In other questions he admitted that the producer / director do have the final say on the music in films, but maintained that sometimes you have to insist you know better than they do about music. He cited Born Free & Goldfinger as songs which wouldn't have been in the movies if they had had their way. He also said that pressure for a hit title song had grown and grown, especially in the JB situation. He confirmed he had been asked to score TND, but told them to stick it when they insisted on somebody else writing the title song. The cimbalom sound in Ipcress File was very much a homage to The Third Man - one of his favourite scores. I think he said Orson Welles was his second wife's godfather!

It wasn't always easy to understand him since he was holding the mike too close and his voice is SO deep! He said that sadly days of sheet music sales were gone and it was now very much a record situation. This was in response to somebody who wanted to know why they couldn't get sheet music to Out Of Africa. He said that back in the days of Born Free they sold thousands of copies. He decided to demonstrate just why, and gave an impression of a youngster banging it out on the piano and calling his mum to listen! He reiterated that arranging and conducting his own music was essential as far as he is concerned. He talked about how the theme for Midnight Cowboy isn't exciting on its own, but it's the rest of the accompaniment and counter-melody which makes it. He loves counter melodies, and mentioned George Gershwin in this connection. I think that was the main highlights.

He then started the signing. I should mention at this point that it was all being filmed by Sky TV, and that the first people we saw go onto the stage posed with him for photos! At this point, Gareth, who cannot stand or sit still for more than 5 minutes, announced that we should go to Piccadilly and watch Across The Sea Of Time at the Imax. He reckoned at that rate of progress, JB would be signing for the rest of the evening (the store shuts at 8 p.m.) and with ATSOT only lasting 40 minutes, we would be back when the queue was considerably reduced. So we left around six for the Imax theatre. Saw the film (which was actually nearer 55 minutes long) and returned to HMV. The queue WAS considerably reduced - it was non-existent, as was JB! We were told he had finished and departed ten minutes earlier.

Geoff.

YOU ONLY LIVE TWICE – An overview

You Only Live Twice, Sean Connery's last outing as Bond for the time being, marked a fairly radical change of direction for John Barry's music score. By now he was an accepted member of the Bond team and expected to conjure up something different for each new film while retaining the familiar sound he had established. This film gave him a welcome opportunity to do just that, by exploiting through music a plot that ranged from Bond's venture into space to his 'marriage'. After limited success with Tom Jones's resounding Thunderball vocal, Barry chose a much gentler, romantic melody on which to base the theme song. He teamed up again with lyricist Leslie Bricusse to produce a beautiful number, which was sung over the opening credits by Nancy Sinatra. Years later, the appearance on the 30th Anniversary double CD of a completely different song entitled ‘You Only Live Twice – Demo’ raised a few questions. The vocal is by an unnamed female session singer, with Barry and Bricusse credited as writers. Leslie Bricusse confirmed that this was their first attempt at the title song, which they eventually discarded, but he could not recall the name of the singer.

However, Graham Rye is not a man to be defeated by any Bond mystery, and after a few plays of the song he was convinced that the singer was Julie Rogers, best known in the UK for her hit ‘The Wedding’. He was able to track down her manager and husband Michael Black (Don's elder brother) who immediately confirmed that Julie was indeed the uncredited singer. On learning the news, Julie was quick to point out that her recording was not intended for demo purposes only. On the contrary, she was chosen to sing the new Bond title theme on the strength of ‘The Wedding’. As she points out: "Successful TV and recording artists do not record demos!" Her song was recorded at CTS studios, Bayswater with Barry conducting a 60-piece orchestra. Julie believes that only late pressure from the producers resulted in Sinatra taking over.

![[Cubby Broccoli at CTS]](/images/scans/t_cubbyatcts.jpg) Not that Sinatra was at first even second choice. Saltzman brought in a musical advisor, over Barry’s head, and he suggested Aretha Franklin. Barry felt her style wasn’t suitable, and in the end the two producers decided on using Frank’s girl, who had just topped the charts with ‘These Boots Are Made For Walkin’’. Asked about it later, she said: "That was a scary experience. John, whose music I just treasure, wrote the song with Leslie Bricusse, who is an old friend of mine. Cubby Broccoli had known my mother and father for years - he'd been there when I was born. The London Philharmonic played on the session. Real pressure." Pressure indeed. According to the composers, nerves got to Sinatra so badly that numerous takes were needed before a definitive recording was in the bag.

Not that Sinatra was at first even second choice. Saltzman brought in a musical advisor, over Barry’s head, and he suggested Aretha Franklin. Barry felt her style wasn’t suitable, and in the end the two producers decided on using Frank’s girl, who had just topped the charts with ‘These Boots Are Made For Walkin’’. Asked about it later, she said: "That was a scary experience. John, whose music I just treasure, wrote the song with Leslie Bricusse, who is an old friend of mine. Cubby Broccoli had known my mother and father for years - he'd been there when I was born. The London Philharmonic played on the session. Real pressure." Pressure indeed. According to the composers, nerves got to Sinatra so badly that numerous takes were needed before a definitive recording was in the bag.

Presumably for commercial reasons, the Sinatra single release was not the version heard in the film. Instead, a completely new arrangement by Billy Strange was produced in Hollywood by Lee Hazlewood and issued by Reprise - the label owned by Nancy's father Frank. Nancy again: "They did a double-tracked Petula Clark kind of thing on the vocal. It got to be a fairly big record, but they put ‘Jackson’ on the flip side and that became the hit." As a counter to this, Barry released his own instrumental arrangement on a CBS single, but it was the Sinatra effort which charted both in Britain and the States.

One of Barry's former record companies, Ember, attempted to cash in on the success of the film by re-issuing his original recording of ‘007’. As was the case in 1963, it was a picture-sleeve single, but on this occasion the flip-side was ‘The Loneliness Of Autumn’ which had no connection with the film. To increase its chances of success, Ember chose to focus on Barry’s recent Oscar win for Born Free, by including a small picture of the famous statuette on the sleeve as well as crediting him as ‘The 1967 Academy Award Winner’. Alas, it was all to no avail as the record sold in very small quantities, making it one of the rarest Bond singles, particularly in the original picture sleeve.

As usual, the score was recorded at the Bayswater studios of CTS, where Sid Margo acted as fixer for the sessions. The London Philharmonic, in reality, were session musicians brought together by Margo on this and many other occasions to record a Barry score. Margo had worked with Barry on his first film score, Beat Girl, and fixed (or hired) musicians for him nearly every time he worked in England right up until his retirement, shortly after the recording of A View To A Kill. Once he knew the size and structure of the orchestra needed by Barry, Margo would try to engage his regulars for film music sessions. These were tried and trusted musicians who were well used to working under pressure, and most had worked for Barry on many previous occasions. Members of the orchestra on the Y.O.L.T. sessions included the following: Violins: Alec Firman, Sid Sax (leader), Paul Shurman, Erich Gruenberg, Henry Datyner, Leonard Dight, Raymond Cohen, Louie Rosen, Billy Miller, Peter Halling, Joshua Glazier, David Belmann and John Ronayne; Bass: Edmund (Nick) Chesterman; Clarinet: Jack Brymer; Trumpets: Ray Davies, Leon Calvert and Greg Bowen; Trombones: Tony Russell and Nat Peck; Horns: Andrew McGavin, Ian Harper and John Burden; Flutes: Chris Taylor, Jack Ellery and David Sandeman; Bassoons/Oboes: Terence MacDonagh, Ron Waller and Tony Judd; Tuba: John Fletcher; Harp: Marie Goossens; Lead Guitar: Vic Flick; Bass Guitar: Ron Prentice; Mandolin: Hugo Dalton; Percussion: Stan Barrett.

The original soundtrack album provided its own curio in the form of differing final tracks for the British and American markets. While the British album contained ‘Twice Is The Only Way To Live’, an instrumental play-out of the main theme, the American release contained ‘You Only Live Twice - End Title’ (vocal by Nancy Sinatra), which is precisely what cinema audiences heard during the closing moments of the film. All later European reissues corrected the final track title to bring it in line with the American album, but the record itself still included the instrumental. More recently, EMI have issued the album on CD, and on this occasion the credits and the music coincide to include the Sinatra vocal.